I was born in the early 1980s in New Zealand. My father was a forest ranger and one of my earliest memories is standing at the edge of a looming pine forest. My parents are Fundamentalist Christians and raised me in those beliefs. Ultimately I think religion and New Zealand were the strongest influences on me growing up.

My Dad got a job as a builder and we moved to the city. I guess we were roughly lower middle-class. My Dad worked two jobs and Mum sewed a lot of our clothes. Later, Dad got a job as the property manager of a girls high school so we moved again. My brother and sister and I were now going to school in a wealthy part of the city. Geographically we hadn’t moved very far but it felt like everything had changed. Rich kids lived completely different lives.

After high school, I studied Communications at university which ended up being almost too general a degree to get a job. My Christian upbringing had taught me I should serve God, so I got an internship at a Christian music company and after that worked at a conservative Christian thinktank. When I got let go by the thinktank I found a job as an “Internet Marketing Consultant”.

Digital marketing in the mid-2000s was stuff like search engines and online advertising. I didn’t know anything about those things but I learned. Internet marketing felt like a new industry that was growing. I seemed to be ok at it, and I liked feeling good at something.

Eventually I got the chance to manage people. It was hard. I never received any formal training; one day I wasn’t a manager and then the next day I was. I wasn’t particularly great at managing people but I liked the feeling of being an Important Manager-Type Person. I started working harder and longer. I had mornings where I would sit at the bus stop with a tight chest, feeling like I couldn’t get one good deep breath. It never occurred to me at that time that I might have been struggling with stress & anxiety. No one I knew talked about that sort of stuff. I just assumed it would pass and that I needed to push through it.

In 2008 I ran myself into the ground and got glandular fever. I failed to recover from that and was diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome or CFS. CFS, or ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis), was barely understood back then. My ME/CFS meant I was really struggling to do my job. Eventually the head of my department had to demote me and take over my responsibilities. I felt like a failure.

My doctor told me to take up jogging to treat my chronic exhaustion, something doctors these days would never recommend for ME/CFS. It was a cheat, I would feel exhausted & fatigued, go for a run and then live off the adrenaline for a few days, then repeat the cycle. At the time I thought I had found the solution to my health problems, so in the early 2010s I left New Zealand and moved to the UK.

It took seven months but eventually I found a job in London doing web analytics. I liked web analytics but felt like at times I would be a better analyst than a consultant. I met the woman who would become my life partner and I started to feel settled in Britain. I felt like I needed to find a job that more directly “served God” so I started looking for roles in the charity/non-profit sector.

A housemate at the time recommended I see if there were any jobs with Alpha International. Alpha International is a Christian charity based in London which develops & promotes a course introducing people to Christianity. They were looking for a social media manager. I could only remember a little bit about the course but I was intrigued. I thought maybe managing social media would suit the soft skills I had and I liked the idea of working for a Christian charity so I applied & got the job.

As I wound down my web analytics job, I was working hard to get a project finished which required a lot of repetitive computer tasks. I started experiencing severe pain in my right forearm and then the same pain in my left forearm. I was forced to go on permanent sick leave before finishing up at that job and started seeing physios & specialists to find out what was wrong with my arms. The diagnosis at the time was that it was RSI or Repetitive Strain Injury. I learnt to operate a computer via voice dictation and asked Alpha International if we could delay my start date in order to give my arms time to heal.

I tried to be brave, and hoped God would miraculously heal me, but I was frightened. Getting ME/CFS originally had been traumatic and I think I was having flashbacks to that with the RSI. I was afraid to tell people just how severe it was. I didn’t want my partner wondering how I was going to “provide” for us. I didn’t want Alpha International to start having doubts about offering me the job.

Eventually Alpha International were like “when can you start?”. My arms weren’t getting any better but the hope was I could rehabilitate them at the same time as starting my new role. This meant from the outset I was going to have to use voice dictation to use my computer. The first time trying to use voice dictation in a dead quiet open plan office was embarrassing, it took just 20 seconds for me to realise that it was never going to work. I had a hilarious meeting with an accessibility adviser who told me I could wear a special hood over my head that would muffle the sound of my voice. Eventually I found a dusty cramped video tape archive room where I was safe to do voice dictation and that became my working space for the next three years. For my arms I would see specialists, have different tests, and try different medicines but none of it helped. To this day I am still reliant on voice dictation software and a foot mouse to use a computer.

Alpha International was connected to a church called HTB or Holy Trinity Brompton. At the time I felt pretty neutral about this, as far as I knew I would be working for Alpha International. On my first day on the job I found out I would be working for both Alpha International and HTB. This seemed a bit odd, but I wanted everyone to like me & didn’t want to cause problems so I didn’t say anything about it.

Doing social media for HTB turned out to be a stressful time suck. It was an unrewarding grind that had an obvious contradiction at its core: I did not attend HTB Church. It was like working for one football team but supporting another. Your employers knew they had your loyalty because they paid you, but they also wanted you to be loyal in your heart. When I reflect on why I let myself get stuck in that situation, the answer is because of my lack of self-worth. I wanted to be Successful Social Media Guy For A Large Church In London. I was willing to put up with a lot to have that.

After two years of some hits & misses I was tired of being stretched too thin and not getting enough support from my managers. Maybe social media management looks different elsewhere, but for me it was nearly all stakeholder and online reputation management. All for a church I didn’t know or like. I requested a shift back to analytics work, but by that time the web development and analytics work was in the process of being outsourced from the organisation entirely. And if you think doing social media management via voice dictation is hard, try working on spreadsheets. I couldn’t deliver in my role, but I had no idea how I was going to get another job. I was miserable.

In 2016 my ME/CFS symptoms got worse. Like when I first got glandular fever, I was running myself into the ground again. I had a meeting with the head of the department who said “you’re struggling”, I said “I can quit”, and he said “ok”. And that was it. I was so fatigued, anxious, and unhappy, I leapt at the chance to leave. Ever the conscientious Christian, I worked hard right up until my last day at HTB. I had a severe flareup of my ME/CFS symptoms and my ME/CFS permanently worsened. I have not been able to work ever since.

The following year my partner and I learned that we were going to have a baby. This was exciting but also worrying. We knew we weren’t going to be able to do it alone because of my poor health so we left London and moved in with her parents.

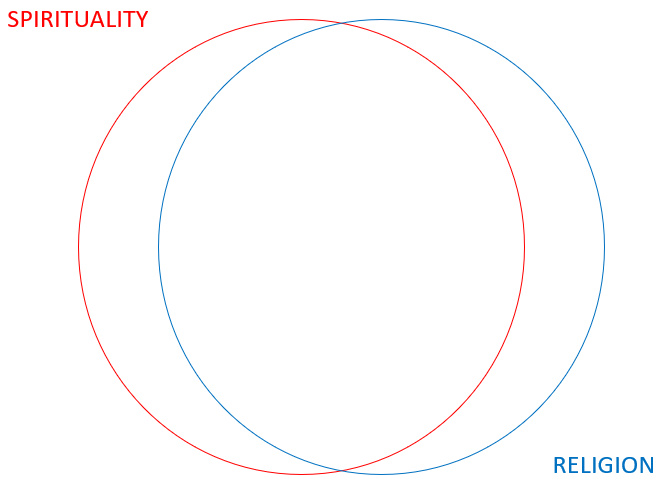

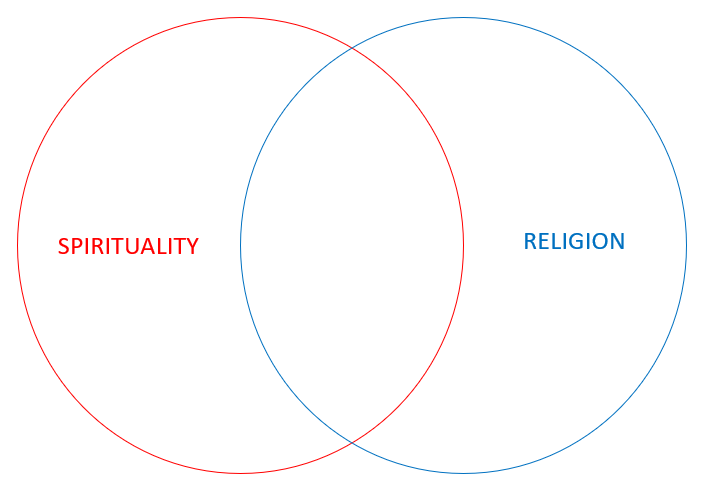

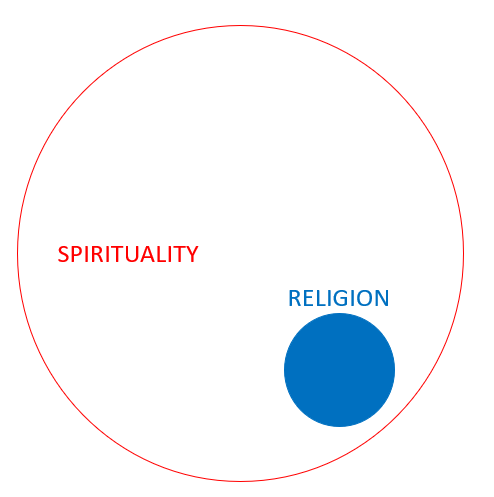

When you are chronically ill, you spend a lot of time with yourself. I started thinking a lot about my Fundamentalist Christian beliefs. I discovered online a movement within Evangelical Christianity of people going through what they called “deconstruction”. It seemed to be about practicing Christianity free from Christian culture. But I realised my issues weren’t just with Christian culture. I was becoming deeply skeptical of the idea of faith. Most Christians I knew had been brought up Christian and described their faith in terms of feelings. The more I thought about it, the more I began to think faith was something believers constructed in their minds.

I decided to take a break from being a Christian. I felt I had nothing to lose, if Christianity was true, I figured, then I would find myself drawn back to it. My break became an indefinite separation. I noticed the only time I would actively think of God was when I was afraid and would start to pray out of habit. Eventually I had to explain to my partner, who is a practicing Christian, that I no longer believed.

My personal view is that I was indoctrinated into Fundamentalist Evangelical Christianity by my parents from birth. This indoctrination meant I was taught from the moment I was born that some of the signals from my brain were not from me but were from “spirits”, or even God Himself. This created a kind of split in my mind where things I did or thought that were contrary to the “Law of God” were because of my failure to properly trust God, but things that were good or fun or rewarding were solely because “God was good”, and He had made these good things for us. I was taught that I was a wretched sinner wholly reliant on God’s mercy & forgiveness. For me personally, belief has had a very negative effect on my self-esteem.

It has been instructive to notice that one of the things I have struggled with most with post-Christianity is fear of death. I have reluctantly accepted that the most likely thing that will happen when I die is that my consciousness will end immediately. Having spent 35 years believing I would live forever, mortality has been a hard pill to swallow. What comfort or consolation exists in the face of death is something I am still exploring.

![A scan of the painting 'Agony in the Garden' by Corregio https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agony_in_the_Garden_%28Correggio%29.

"[T]he painting was admired by Vasari in Reggio Emilia - he described it as:

a small painting one foot tall, the rarest and most beautiful thing, in which can be seen his small figures and Christ in the garden - the painting is set at night, with the angel appearing and by the light of his splendor illuminating Christ, who is shown so real and so true that it is impossible to imagine him being expressed better. At the foot of the mountain, on level ground, are three sleeping apostles, above whom he shows Christ praying, which gives an impossible strength to the figures; and even more so, in the background, he shows dawn rising and soldiers coming with Judas from one side of the painting: and in such smallness and with such intensity does he show this story, there is no work that is its parallel for patience and hard work."](https://oblivionwithbells.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/oracion_en_el_huerto_correggio.jpg?w=944)